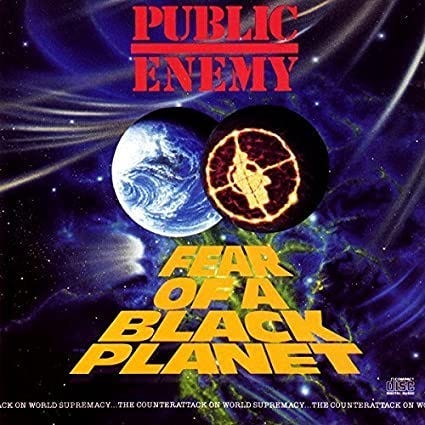

Backspin: Public Enemy — Fear of a Black Planet (1990)

Public Enemy ushered in a decade with an album that viscerally captured the moment. It’s also urgently relevant today. (92.5/100)

Originally published 5/31/20 on Medium.

As the 20th Century rounded into its final decade, the racial powder keg that informed so much of the century’s discord appeared poised to blow. Virginia Beach was recoiling from riots sparked by police brutality. Black New Yorkers were still smarting from the racially charged killings of Yvonne Smallwood, Latasha Harlins, Edmund Perry, Michael Griffith and others. Ronald Reagan and George Bush paved paths to the White House exploiting racial stereotypes to incite fear and resentment in a white working class spooked by its eroding relevance.

Having emerged as the face of politically charged rap with the runaway success of their unrelenting sophomore masterpiece, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Public Enemy responded with an album that was at once viscerally of the moment and presciently ahead of its time. Fear of a Black Planet tackles the tensions and controversies of its era head on. But it also dives unapologetically into the historical, sociological, and biological subtexts that shape our perceptions and conceptions of race to this very day, in which American cities burn 30 years after its release.

I didn’t intend to revisit Fear of a Black Planet as part of the Backspin series. At least not this close on the heels of reviewing Nation of Millions. In a moment where the murders of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd are set against the backdrop of a pandemic disproportionately afflicting communities of color, the album called to me. I needed to immerse myself in its dense layers of sonic dissonance, exhale through its cathartic defiance, absorb its cerebral depth and thematic nuances.

The whistling wind that introduces the opening instrumental, “Contract On The World Love Jam,” evokes desolation. It’s followed by the muted toll of synthetic bell: a solemn wake up call seemingly calibrated to reorient a stupefied nation to a dystopian future, which somehow became a dizzying present. The beat staggers in, not like the defiant war drums of Nation of Millions that were fit to score a riot, but like the weary rhythm of a world weighed down. It’s the rhythm with which you maneuver a landscape where furtive glances from passersby give way to adjustments of face masks; where fires burn in streets as they wither in souls. Voices cascade in and out of the mix, crossing decades and continents, culminating in a resolute proclamation: “there is something changing in the climate of consciousness on this planet today.”

Then it happens. The tension that has been ever-so-subtly building throughout the intro erupts into the throbbing percussion and stabbing guitars of “Brothers Gonna Work It Out.” The album’s third single makes for a resounding opener; dissonant and atonal, but anchored by a persistent beat that keeps marching forward through the tsunami of sonic curveballs hurled in its path by the Bomb Squad. It still takes me a full minute to get acclimated amidst the storm of sound, but it’s the precisely the storm I found myself needing to chase. At once a call to action, an anthem of empowerment, and a show of solidarity, “Brothers Gonna Work It Out” embraces the frustration and trauma baked into black manhood and channels them into a controlled rage that leaves little doubt that we shall not only overcome, but triumph.

The remainder of the album constitutes a whirlwind rollercoaster ride through all that must be surmounted. The funk fueled groove and madcap chorus of the Flavor Flav fronted “911 Is a Joke” belie its incisive commentary on the double standards of first responders, often still slow to respond to emergency calls in inner city neighborhoods. Though delivered with Flav’s inimitable aplomb, the statement is clear though the hashtag was decades away: “black lives matter.”

“Incident at 66.6 FM,” puts a beat to snippets from a radio interview of Chuck D by former Fox News commentator, Alan Colmes. Colmes’ condescension and the hostility of his callers mirror the tenor of too many conversations with and about outspoken black figures to this day, and set the table perfectly for MistaChuck’s magnum opus.

“Welcome to the Terrordome” is equal parts manifesto and mission statement, setting the tone for what Chuck anticipated to be a decade of tumult (the “Terrordome” representing the dawning ’90s) and drawing a clear line in the sand between the righteous and the wicked. Over a swirling track that feels like the trademark “noise” of Nation of Millions turned inside out, he unleashes:

It’s weak to speak and blame somebody else

When you destroy yourself

First nothing’s worse than a mother’s pain

Of a son slain in Bensonhurst

Can’t wait for the state to decide the fate

So this jam I dedicate

To places with the racist faces

Example of one of many cases

The Greek weekend speech I speak

From a lesson learned in Virginia (Beach)

I don’t smile in the line of fire

I go wildin’

But it’s on bass and drums, even violins

What you do is get your head ready

Instead of getting physically sweaty

When I get mad

I put it down on a pad

Give ya something that ya never had

Controllin’

Fear of high rollin’

God bless your soul and keep livin’

In a catalog stacked with seismic singles, “Welcome to the Terrordome” may be PE’s most potent. It leaves me simultaneously fired up and rung out, but it never fails to make me feel, even in these most numbing of moments.

Cognizant of creating an album that mirrored the peaks and valleys of their live show, the group wisely dials the fervor down a notch with “Meet the G That Killed Me,” a short but potent cautionary tale about a deadly virus disproportionately ravaging black communities. Whether it’s AIDS or COVID, the genesis of the problem is the same. Threats to marginalized populations are not treated with appropriate urgency by those in power, and often not within the afflicted communities.

“Pollywanacracka” grinds to an even more deliberate pace, settling into a murky funk groove. Chuck channels There’s a Riot Goin’ On era Sly Stone to narrate a multi-perspective meditation on the stigmas surrounding interracial relationships in the black community. The third verse widens the lens, placing the rancor in a larger societal context: “This system has no wisdom, the devil split us in pairs/And taught us white is good, and black is bad/And black and white is still too bad.”

It’s one of the first explicit allusions to the album’s titular theme: the existential fear of blackness in which racism is rooted. According to Chuck D, the concept for the album is culled from Dr. Mary Frances Cress’s Theory of Color Confrontation. Cress’s theory holds that racism grows out of a latent inferiority complex stemming from the hyper awareness of whites of their melanin deficiency and status as the global minority. That insecurity leads to acts of “repression, reaction formation, and projection.”

The most obvious form of repression comes through law enforcement, which has evolved from slave patrols to Jim Crow laws to knees on necks. Chuck succinctly snapshots the pathology on the blistering “Anti-Nigger Machine.”

“Burn Hollywood Burn” lobs a hand grenade at a the subtler subjugation manifested through images and stories. A Hollywood studio system that literally emerged into mainstream American culture by portraying black men as predators in Birth of a Nation makes for an easy, if deserving, target. But it’s Chuck’s sidebar for the broadcast media that resonates the loudest in a moment when black civil disobedience is decried as rioting while armed white insurgents storming state houses are covered as “protesters:

Get me the hell away from this TV

All this news and views are beneath me

All I hear about is shots ringin’ out

About gangs puttin’ each others’ head out

Side 2 kicks off with an under appreciated trifecta of tracks as profound as they are powerful. “Who Stole the Soul?” cranks the BPMs to methamphetamine levels and Chuck delivers an impassioned screed decrying the systemic trickery — from tax penalties to white flight — deployed to keep the American dream just out of reach to black hands.

The title track returns to the topic of miscegenation, this time as a conduit to explore the browning of the planet. As the sample on the chorus highlights, a baby born to a white parent and a black parent is black. Part of the inherent “fear” of the eventual extinction of the white race, the song posits, stems from the awareness of the dominance and resilience of black genes.

But it’s “Revolutionary Generation” that may be the most overlooked song in PE’s vast catalogue. A fierce critique of the abuse of black women throughout history and the division it has sown within black families and communities, the song doesn’t let black men (including PE themselves) off the hook. Yet, it digs deeper, identifying the root of the division in the systematic destruction of black families during slavery.

Why is it that we’re many different shades?

Black woman’s privacy invaded

Years and years

You cannot count my mama’s tears

It’s not the past, the future’s

What she fears

Ultimately the songs sounds a conciliatory note, anchoring the path forward in strong families and mutual respect between men and women.It’s followed by Flav’s absurdist lark, “Can’t Do Nuttin’ For Ya Man,” which underscores the theme with its opening vignette about a brother down on his luck after stepping out on his wife one time too many.

The album moves briskly from there. “B-Side Wins Again” champions underground music as the true conduit for messages of empowerment, often hidden in plain sight on the flip side of a commercial single. The propagation of racism through corrupted educational and religious institutions is called out on the frenetic “War At 33 1/3.” But the album’s final lap feels like a run up to its iconic closer.

“Fight the Power,” already an anthem by the time the album dropped, is the outlet we don’t know we’ve been craving. We’ve spent an hour learning exactly what we’re fighting, in all of its nuances and contradictions. Now, with the cascading drums pounding and the thick bassline rumbling, we’re ready to fight. It’s a battle that will be won not with fists and firearms, but the more potent weapons of knowledge, wisdom, and understanding. We’re armed for combat thanks to one of hip-hop’s most conceptually sophisticated albums.

As the rhythm’s designed to bounce

What counts is that the rhyme’s

Designed to fill your mind

Now that you realized the pride’s arrived

We got to pump the stuff to make us tough

From the heart

It’s a start, a work of art

To revolutionize make a change

Nothing’s strange

People, people we are the same

No we’re not the same

’Cause we don’t know the game

What we need is awareness, we can’t get careless

You say what is this?

My beloved, let’s get down to business

Mental self defensive fitness

Fear of a Black Planet offers a lot to digest, sonically and intellectually. Despite the presence of several standout singles, the album is really meant to be absorbed as a whole, playing out like a dizzying collage of sound that communicates just as powerfully through its aural textures as its lyrical dissertations. That might be why it doesn’t enjoy the perennial reverence reserved for Nation of Millions. It’s not an album you play in the car while running errands or in the background during Sunday cleaning. It’s not an album you seek out.

It’s an album that calls to you when the tangle of unresolved divisions and unspoken pathologies threatens to overwhelm a planet becoming darker with each passing year. It’s the therapy, the treatise, and the catharsis that you crave when blackness is a capital crime for a jogger in Georgia, and whiteness is weaponized against a birdwatcher in New York City. It’s a reminder to keep fighting the power, because despite the horrors of the terrordome, the brothers (and sisters) gonna work it out.

By the Numbers

Production: 10

Lyrics (how the words are put together): 9

Delivery & Flow: 9.5

Content (Substance): 10

Cohesiveness: 10

Consistency: 9

Originality: 10

Listenability: 8.5

Impact/Influence: 6.5

Longevity: 10

Total — 92.5

Backspin is a look back at the albums that shaped and defined hip-hop. It explores what made them resonate, the impact they had on the culture, and where they fit in today’s ever-expanding hip-hop canon.

In my opinion, this has got to be one of the most influential albums in Hip Hop. Public Enemy changed the genre.

“War At 33 1/3”, Bomb Squad is my favorite Bomb Squad