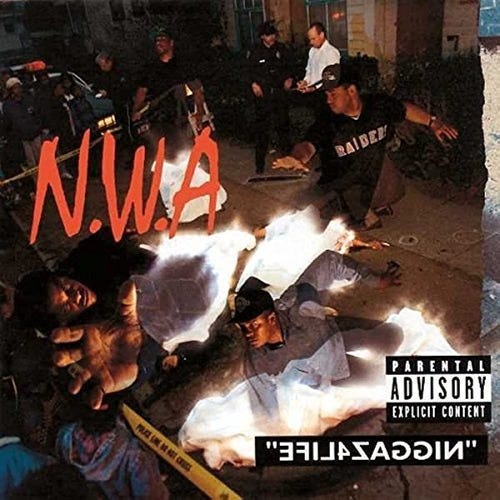

Backspin: N.W.A — Efil4zaggin (1991)

Gangsta rap’s course changing crossroads (80/100)

Originally published 2/3/24 on Medium.

Efil4zaggin is one of hip-hop’s most confounding albums. It detonated in Spring of ’91 like an atom bomb. The ensuing mushroom cloud engulfed the entire hip-hop landscape. The entirety of popular culture soon followed.

Album for album, ’91 is quietly one of hip-hop’s most compelling years. Yet, the sheer force and potency of N.W.A’s second and final full length release instantly overshadowed all that came before it. The year’s subsequent releases, including a few certified classics, were relegated to the outskirts of an ecosystem radiating with N.W.A’s singularly nuclear brand of bravado.

Efil4zaggin’s unrepentantly outsized gangsta boogie effectively obliterated conscious rap’s unlikely commercial foothold, despite a spirited late-year last gasp by Public Enemy. It elbowed the musically and culturally progressive stylings of left-of-center iconoclasts like the Native Tongue collective to the “alternative” fringes.

Selling nearly a million copies in its first week, Efil4zaggin solidified gangsta rap as the commercial face of hip-hop — a jarring juxtaposition to MC Hammer’s sequined parachute pants and flamboyant dance routines that marked rap’s emergence as a mainstream juggernaut just a year prior. In doing so, Efil4zaggin is often tagged with stripping gangsta rap of the strident social commentary that underscored its ’80s iterations and contracting it to cartoonishly reductive caricature.

While N.W.A’s countless disciples unquestionably oversimplified the formula, Efil4zaggin is a far more complex work than it gets credit for. Intentionally or not, N.W.A’s swan song effectively offered two paths from which subsequent gangstas could choose. How much culpability does N.W.A hold for the choices of the next generation (and their record labels)?

Efil4zaggin bursts from the starting block with the velocity of a shotgun blast. After “Prelude” quickly lays to rest any apprehension that N.W.A might stumble following the 1990 departure of star MC and primary writer Ice Cube, the remaining four deliver a mesmerizing treatise on the tao of gangsterism in one of hip-hop’s most relentless opening song sequences.

“Real N****z Don’t Die” and “N****z 4 Life” deliver a 1–2 punch of a dissertation on the epistemology and attitude behind the word that instantly made their group’s name a new lightening rod in a generations old debate.

The former is a cacophonous anthem of chest-thumping machismo. Atop Dr. Dre’s sonic tsunami consisting of no less than 10(!) credited samples, Dre, MC Ren, and Eazy-E seize defiant ownership of the word weaponized for centuries to disenfranchise. In verses evoking police harassment and the criminal justice system as symptoms of systemic oppression, the MCs position their outsized bravado as a survival mechanism. The opposite of respectability politics, the ethos of gangsta rap as espoused by N.W.A seems to be “don’t try to assuage their fear; wield it as your weapon.”

The latter dials back the sonic pyrotechnics. Leaning heavily on a sped-up rendering of the ominous bassline from Parliament’s “Sir Nose D’Voidoffunk,” the track delivers a surgical explanation of the Black community’s cooption and subversion of the most American of epithets. The three MCs embrace the word as an acknowledgement of their ongoing struggle, a celebration of cultural resilience, and a thumb in the eye to an establishment bent on perpetuating the practices of the past.

[MC Ren]

Why do I call myself a n****, you ask me?

Well it’s because motherf***ers wanna blast me

And run me outta my neighborhood

And label me as a dope dealer, yo, and say that I’m no good

But I gave out jobs, so n****s wouldn’t have to go out

Gave ‘em some dope and a corner, so they could show out

When the cops came, they gave a fake name

Because the life in the streets is just a head game

“Appetite For Destruction” thrusts the ethos of the previous two tracks into action. At once sharply aggressive and coldly menacing, Dre’s production is a meticulously calibrated exercise in controlled chaos. Lyrically, Dre, Ren, and Eazy savagely lay waste to any and all adversaries, whether on the mic, in the street, or from the establishment. While not as anthemic as the group’s 1988 assault, “Straight Outta Compton,” “Appetite For Destruction” is every bit as bracing.

In Ice Cube’s absence, Dr. Dre establishes his production as the true star of Efil4zaggin. With lead single “Alwayz Into Somethin’,” Dre spins a breaking curveball providing a much needed break from the unrelenting intensity of the album’s first leg. If the slippery synths of The D.O.C.’s “No One Can Do It Better” represented Dre’s first step toward the G-Funk sound that he would soon make his signature, “Alwayz Into Somethin’” is a full on long jump.

Mid-tempo percussions percolate. A persistent rhythm guitar builds tension. It culminates in elongated synth lines that resolve into a punctuative horn sample from Bob James’ “Storm King” backing staccato adlibs from Jamaican chatter Admiral Dancehall. In sharp contrast to the bombast of the early tracks, Ren and Dre seep into the contours of the beat with the slow rolling ease of warm maple syrup, evoking late night creeps as unhurried as they are untoward.

Ice Cube’s unique combination of charisma and ferocity would have shined atop the immaculate soundscapes of the opening song suite. Yet, the sheer intensity of the remaining 3 mic wielders combined with the potency of The D.O.C.’s pen as the Cyrano de Bergerac behind Dre’s unexpectedly assured emergence as a full-time rapper allows Cube’s departure to fly largely under the radar. The most glaring signal of Cube’s absence is the incessant string of disses fired his way.

The beef culminates in “Real N****z,” a rumbling war cry punctuated by DJ Yella’s surgical turntablism. The actual disses lean towards the generic, at times even tepid (“We started out with too much cargo/So I’m glad we got rid of Benedict Arnold”). But the track still lands as a potent salvo thanks to the urgency of Ren and Dre’s rapid fire back and forth and the rhythmic pugilism of the production.

“Alwayz Into Somethin’” music video, 1991 (Image from Ruthless/Priority Records)

Had N.W.A carried the sound and fury of the album’s first half into its second, they may well have crafted a sophomore opus to rival their debut. Instead, the back nine takes a sharp detour, stumbling with nearly the same velocity the front end soars.

In the cases of “One Less B****,” “Findum, F***um and Flee,” and “She Shallowed It” the book can be judged by its cover — or rather the song by its title. N.W.A venture into 2 Live Crew territory with graphic tales of sexual exploits. But where the Miami posse built its brand on raunchy camp, N.W.A marry their smut with the jarring brutality of their patented gangsta rap. The mash-up proves tonally awkward. Killing women is the antithesis of gangsta and undercuts the hyper masculine posture of the early tracks. The members’ persistent references to their own ejaculate are as puzzling as they are redundant.

When over-the-top sex rhymes work, they’re generally cut with cleverness (see $hort, Too). Here, the wit is painfully absent. “Automobile” and “I’d Rather F*** You” fall flat in their attempts to send up P-Funk excursions (Parliament’s “Automobile” and Bootsy’s Rubber Band’s “I’d Rather Be With You” respectively). Given the inherent transgressiveness of P-Funk, neither record feels as irreverent as the original, underscoring that vulgarity doesn’t necessarily equate edge and you can’t parody a parody.

The cringy detour ends as abruptly as it begins with a pair of album-closing standouts. Sonically, “Approach To Danger” is one of Dre’s most arresting concoctions. Foreboding keys, piercing strings, and filtered screams converge into a symphony of depravity. Staccato drums pound with the ferocity of a bareknuckled brawl. In stark contrast to the devil-may-care revelry of the album’s earlier murder sprees, the stark vignettes of brutality are chilling in their matter-of-factness. It’s as if, on the album’s penultimate offering, we’ve reached the inevitable erosion of the soul inherent in the earlier embrace of gangsta tropes.

“Dayz of Wayback” closes the album with an origin story. Circling back to the earlier themes of self-definition, Ren and Dre paint pictures of a community in decay. It feels as though they’re speaking for a generation when detailing their embrace of brutality in the name of surviving it.

[Dr. Dre]

When I was a kid and puttin’ my bid in

Yo, Compton was like still waters — discretely calm

Now it’s like motherf***in’ Vietnam

Everybody killin’, tryin’ to make a killin’

N****s stealin’, motherf***ers wheelin’ and dealin’

With so many ways to come up

The average n**** didn’t give a f***

About another motherf***a in this game and

Claimin’ what he claimin’, livin’ like he livin’, killin’ after killin’

Murder was a dirty job, to rob a dead man was the best plan

’Cause a dead man never ran

But now your best friend is your worst friend

Greed, kids to feed, make ’em need mo’

Efil4zaggin was a divisive album from the moment it dropped. Yet, few of its acolytes or critics truly grappled with its duality. While true heads embraced the lyricism of the more substantive tracks, casual fans and cultural dabblers latched onto the shock, awe, and gimmickry of the extended detour.

For suburban teens in search of vicarious thrills and performative rebellion, the over the top antics made for easy cooption. A full unpacking of the truly challenging moments — far more nuanced and subtext heavy than a broad “F*** Tha Police” — would have required a level of critical discourse mainstream fans and critics alike were still reticent to grant hip-hop.

Ice Cube’s absence is perhaps most conspicuous not in what he might have added, but what likely would not have made the cut had he remained. By ’91, Cube was a disciple of the Five Percent Nation. His 1990 solo debut, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, pioneered a revolutionary but gangsta ethos, in which scathing social commentary was couched behind a gangsta aesthetic. It’s hard to imagine 20 minutes of pointless debauchery making the final tracklist with him in the fold.

Without that 20 minutes, Efil4zaggin would be a taut, relentless marriage of chest-pounding machismo and paradigm-challenging concepts that may well have set gangsta rap on a course of true social disruption rather than salacious distraction.

It would have denied critics easy talking points with which to sully hip-hop and lesser artists the option of an easier, if decidedly lower road to gangsta rap stardom. Instead, in what proved to be their swan song, N.W.A paved that lane. For the remainder of the decade, the low road would remain bumper-to-bumper like the 405 in rush hour.

By the Numbers

Production: 10

Lyrics (how the words are put together): 8

Delivery & Flow: 8.5

Content (Substance): 7

Cohesiveness: 6

Consistency: 7

Originality: 8

Listenability: 8

Impact/Influence: 10

Longevity: 7.5

Total — 80

Backspin is a look back at the albums that shaped and defined hip-hop. It explores what made them resonate, the impact they had on the culture, and where they fit in today’s ever-expanding hip-hop canon.